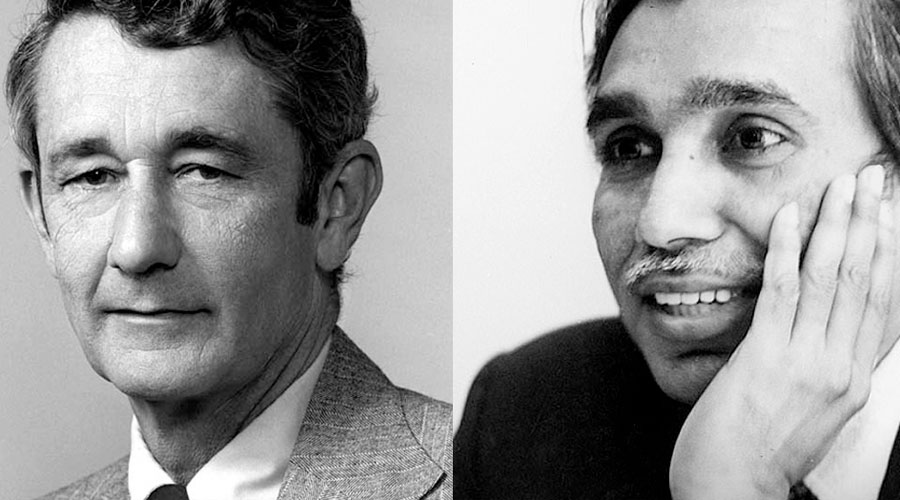

Graham promoted the creation of a computerized program called Building Optimization Program (BOP), aimed to cut down the construction costs. This program was designed as a diagnostic tool by which architects and engineers could identify the points where constructive costs could be cut down, but, of course, it was accused on its the main priority, that was the economy rather than the project.[…] Also the introduction of Computer-Aided Design and of its possibilities was the result of a collaboration between Graham and Khan. The use of computers by SOM dates back to the early fifties and to the construction of the Academy of Aeronautics. In the following years, with the development of research, computers entered in SOM, as happened in many companies, initially through the administrative sector. In 1963 SOM installed an IBM-1620 that was used for the study of complex structural systems, energy requirements and for financial planning. Khan, Graham and a third partner, Richard Keating, were convinced that computers would have also other applications, thus decided to invest in updating the equipment of SOM. When, in the mid-seventies, were first CAD programs was developed, SOM began to engage programmers and computer experts. In 1980 Douglas Stoker made a presentation to the partners including a spectacular fly-thought, on three screens, of the city of Chicago, that led to the preparation for the partners of a booklet based on the potential of informatics. Stoker became a partner in 1984 and SOM formed a joint venture with IBM for the development and sale of software and services. Later, there was a transformation of the market in which this initiative was moving. From a recollection of John Zils, associate partner and currently in charge for the group of structural engineers SOM Chicago: “many people began to realize that computer software would have produced a lot of money and they threw themselves into this market [investing in research] with a force that for us became impossible to compete with them.” As a result, SOM sold its system to IBM. However, says Zils: “this sale still remains something difficult to stand. We were used to create our own software customized for what we wanted to do… And now we are dependent of others who do things for us and that, of course, are not in the way in which we want them. We are always having to evaluate different software to find the one that better fits to our needs.

Early software customisers at SOM

From ADAMS N., Skidmore, Owings & Merrill: SOM since 1936, Phaidon Press, 2007. (From the Italian version. Translation by Alberto Pugnale. Apologies for not being able to find the original text in English).

PERSONALIZZATORI PRECOCI, Nuovi strumenti (2)

“Graham fu promotore della creazione di un programma computerizzato denominato Building Optimization Program (BOP), finalizzato all’abbattimento dei costi di costruzione. Questo programma era studiato come uno strumento diagnostico mediante il quale architetti e ingegneri potevano individuare i punti nei quali i costi esecutivi potevano essere tagliati, ma, naturalmente, attirava l’accusa che la priorità principale fosse l’economia più che il progetto.[…] Anche l’introduzione delle possibilità insite nella progettazione computerizzata fu il risultato della collaborazione tra Graham e Khan. L’uso dei computer da parte di SOM risale ai primi anni cinquanta e alla costruzione dell’Accademia dell’Aeronautica. Negli anni successivi, con lo sviluppo della ricerca, i computer entrarono da SOM, come accadde in molte aziende, inizialmente attraverso il settore amministrativo. Nel 1963 SOM installò un IBM-1620 che veniva utilizzato per lo studio di sistemi strutturali complessi, dei fabbisogni energetici e per la gestione progettuale e finanziaria. Khan, Graham e un terzo partner, Richard Keating, erano convinti che i computer avrebbero avuto anche altre applicazioni, quindi decisero di investire nell’aggiornamento della dotazione informatica di SOM. Quando, a metà degli anni settanta, furono elaborati i primi programmi CAD, SOM cominciò ad assumere programmatori ed esperti di computer. Nel 1980 Douglas Stoker fece una presentazione ai partner comprendente uno spettacolare fly-throught, su tre schermi, della città di Chicago, che portò alla preparazione ai partner di una brochure sulle virtù della tecnologia informatica. Stoker divenne partner nel 1984 e SOM formò una joint venture con IBM per lo sviluppo e la vendita di servizi e software informatici. Successivamente, intervenne però una trasformazione del mercato nel quale questa iniziativa si muoveva. Come ricorda John Zils, associate partner e attualmente responsabile del gruppo strutturisti di SOM Chicago, “molta gente cominciava a rendersi conto che i software per computer avrebbero fatto moltissimi soldi e ci si buttarono [investendo denaro e ricerca] con una forza tale che per noi diventò impossibile competere”. Di conseguenza, SOM vendette il proprio sistema a IBM. Tuttavia, dice Zils: “ancora oggi la vendita rimane una cosa difficile da digerire. Eravamo abituati a crearci da soli il software su misura per quello che volevamo fare… E adesso ci troviamo a dipendere da altri che fanno le cose per noi e che, naturalmente, non le fanno nel modo, in cui noi vogliamo farle. Ci troviamo sempre a dover valutare i diversi software per trovare quello che si avvicina di più alle nostre esigenze.”

Tratto da: ADAMS N., Skidmore, Owings & Merrill: SOM dal 1936, Electa, Milano 2006, pp. 34-36.

L’adattamento del software alle specifiche esigenze del progettista è una necessità che evidentemente risale alla nascita dei computer. Forse ancora più che oggi, queste tecnologie erano viste come un qualcosa che non vincolava la progettazione ma piuttosto permetteva di ampliare gli strumenti progettuali, addirittura lasciando la totale libertà di crearseli su misura.

Un corretto approccio nell’uso dei computer è il primo passo da compiere verso un dibattito critico costruttivo sull’uso delle nuove tecnologie all’interno del progetto architettonico. Noto invece che parecchie tra le più recenti pubblicazioni (vedi Architettura e cultura digitale, vedi DeLanda, ecc…) dimenticano i ragionamenti di Frazer, di Graham e Khan. Questi ultimi addirittura progettisti che non si occupavano nello specifico di ricerca informatica. Sono solo i primi di tanti nomi, tra cui anche l’italiano Luigi Moretti, che quasi mezzo secolo addietro hanno ragionato sull’uso di nuovi strumenti informatici. A questo punto, perché non partire da queste basi invece di uscire totalmente fuori tema, come spesso accade oggi?